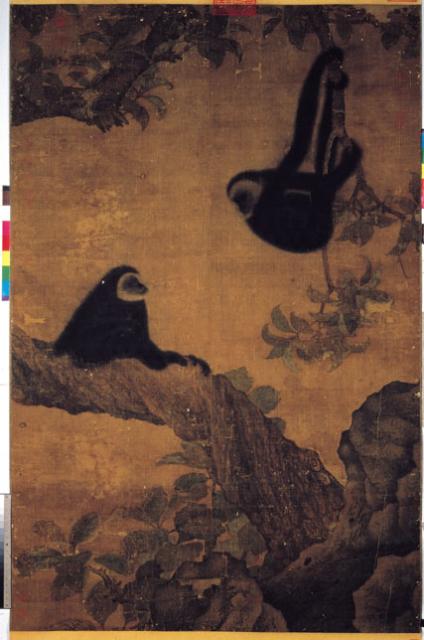

宋人枇杷猿戲圖 軸

推薦分享

資源連結

連結到原始資料 (您即將開啟新視窗離開本站)後設資料

- 資料識別:

- 故畫000194N000000000

- 資料類型:

- 類型:繪畫

- 型式:靜態圖像

- 主題與關鍵字:

- 猿

- 出版者:

- 數位化執行單位:國立故宮博物院

- 格式:

- 本幅 165x107.9公分、全幅 121公分

- 關聯:

- 石渠寶笈初編(養心殿),上冊,頁667 &*故宮書畫錄(卷五),第三冊,頁148 &*故宮書畫圖錄,第三冊,頁113-114 &*1.王耀庭,〈宋人枇杷猿戲圖〉,收入王耀庭、許郭璜、陳階晉編,《故宮書畫菁華特輯》(臺北:國立故宮博物院,1987年初版,2001年再版),頁162-163。 2.王耀庭,〈國之重寶 — 書畫精萃特展〉,《故宮文物月刊》,第19期(1984年10月),頁24-25。 3.王耀庭,〈宋人枇杷猿戲圖〉,《故宮文物月刊》,第100期(1991年7月),頁80。 4.張華芝,〈宋人枇杷猿戲圖〉,收入蔡玫芬主編,《精彩一百 國寶總動員》(臺北:國立故宮博物院,2011年九月初版一刷),頁278。 &*老樹擎空,突出畫幅,其枝垂掛,復返畫中。畫幅中的枝幹,筆不連而意連,足見畫家佈局之匠心。一猿攀枝搖盪,如戲鞦韆。一猿則踞幹悠閒旁觀,真能得猿猴動息之情。畫技精湛,特善用墨,曲盡黑猿毛色之狀,樹石描繪精采、用色雅正,尤有過人處,是宋無款作品中之巨幅精品。易元吉的猴貓圖突顯毫芒畢現的用筆功夫,本畫則用墨功夫一流。&*An old loquat tree rises from the bottom of the painting, its branches projecting outward at the right and left, then re-entering at the top of the composition. The brushwork for the tree, though interrupted, amply conveys the form, thus showing the artist's skill at composition design. Two gibbons—one sitting quietly on the twisting trunk, the other suspended from a slender branch—appear in the open space at the center of the composition. The slender branch, pulled downward by the gibbon, seems to possess a recoil force, the kind a swing possesses when swung back and forth by children. The seated monkey idly watches its companion at play. The rendering of the tree and rocks is also convincing with elegant colors, making this a masterpiece of the finest anonymous Sung works. I Yüan-chi was noted for his controlled and delicate brushwok, while this painting is first-rate in the use of ink.&*從畫面上來看,枇杷樹的枝幹上下各一段,並未相接,觀賞時卻有著相連的感覺,這種畫外之意,正是作者別出心裁的安排。而其沈著的用色、勁健的用筆則將樹幹的扭曲斑剝、樹葉的轉折、石頭的堅硬和猿身黝黑的絨毛表現得栩栩如生,像可以觸摸一般。然只生動地畫出物象的形貌仍不夠,必須掌握其情態,方算傳神,因此畫中黑猿,掛在枝幹上的一隻,手尾緊握,好似在盪鞦韆一般,另一隻則悠閒地坐在樹幹上,和牠相互凝望,情意相繫。&*老樹擎空,突出畫幅,其枝垂掛,復返畫中。畫幅中的枝幹,筆不連而意連,足見畫家布局之匠心。畫中一猿攀枝搖盪;一猿則踞幹慵坐,四目凝望,情意相繫,得猿猴動息之情。畫者特善用墨,曲盡黑猿絨毛之狀,深達寫物之理趣,堪為宋代大幅猿畫之精品。學界據此推論,是軸出自易元吉﹙約活動於11世紀後半﹚之手。易元吉,湖南長沙人,為北宋畫猿聖手,米芾讚其「徐熙後一人而已」。(20110913)&* An old tree arcs through the space, reaching out of the painting, into the upper left, and then back down through the top. The trunk and branches in the work are done with strokes that are not connected but appear to be so, reflecting the ingenuity of the painter in terms of the arrangement. One of the two gibbons swings from a branch, while the other sits quietly on the trunk, their eyes meeting each other’s for a sense of emotional bonding, capturing both the motion and spirit of these primates. The artist was particularly gifted at the use of ink in capturing the gibbons’ black fur with precision via a deep understanding of the subject’s nature. For this reason, the painting stands as a large and important masterpiece of Song dynasty gibbon painting. Scholars have thus suggested that it comes from the hand of Yi Yuanji (fl. ca. 2nd half of 11th c.). Yi Yuanji, a native of Changsha in Hunan, was the greatest master of gibbon painting in the Northern Song, with Mi Fu praising him as “the one and only after Xu Xi.”(20110913)

- 管理權:

- 國立故宮博物院

授權聯絡窗口

- 國立故宮博物院圖像授權、出版授權、影音資料授權-申請流程說明

http://www.npm.gov.tw/zh-TW/Article.aspx?sNo=03003061